New Publications: A Romano-British Saltern at Street House

Exciting research is being conducted as Street House in Loftus, UK. Leader of the project Dr. Steve Sherlock reports on progress in his latest publications titled “Salt Making at Street House in 2023: Guided Walk Information” and “A Romano-British Saltern at Street House NZ 7390–1930.” Both can be found on our research repository or copied below.

A Romano-British Saltern at Street House NZ 7390–1930: Excavations in the Summer 2023

In recent years (2016–22), I have been undertaking excavations on a Neolithic saltern at Street House (Sherlock 2021). Indeed, some readers will recall some earlier excavations at Street House that revealed the evidence for Iron Age salt making at the site (Sherlock & Vyner 2013). It was with that information about a potential pattern of salt manufacture at the site that led to a critical evaluation of the geophysics to assess the potential for other salterns. Further work by James Lawton (AoC Archaeology) suggested there were other locations indicative of kilns or salterns.

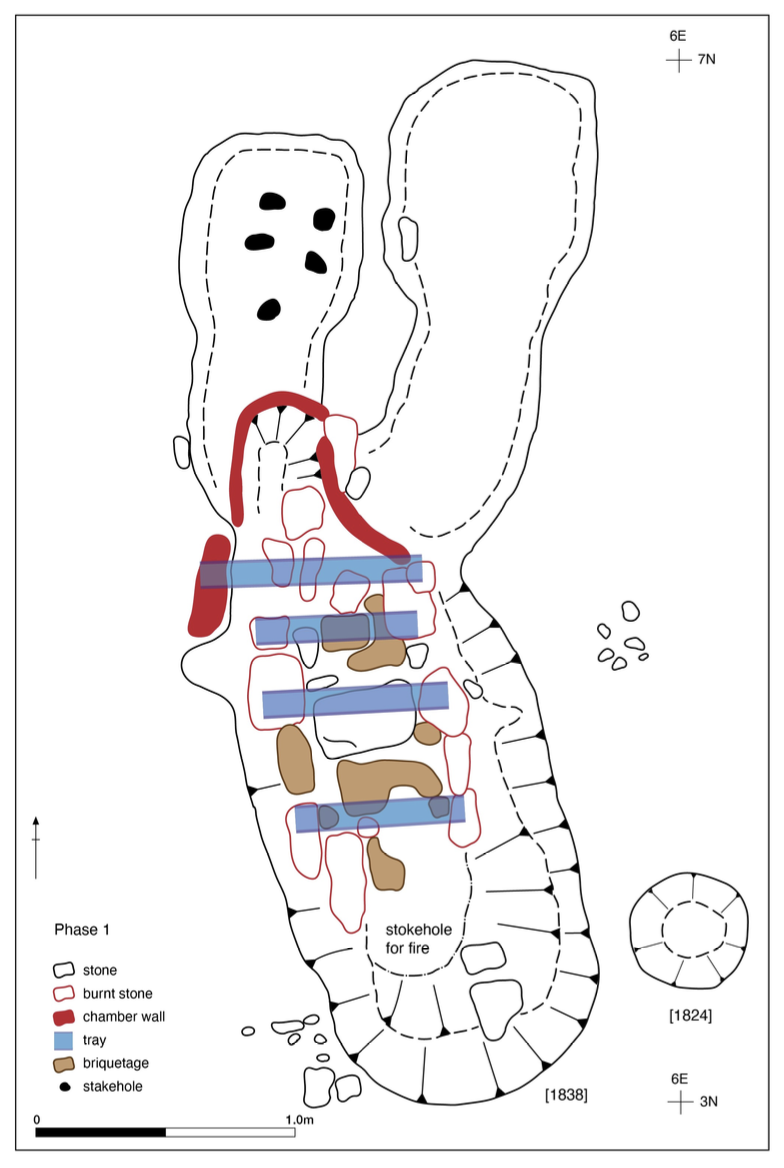

Fig. 1 Plan of Street House Romano-British saltern excavated in the summer, 2023; probable positions where evaporation trays were placed are shown in blue.

An area 12m x 8m was selected for evaluation and excavation by initially stripping the topsoil by machine in late August. The area was located within a known Romano-British enclosure that has been dated to the late fourth century AD and the provisional dating of the pottery is in accord with that Late Roman date. The full excavation account will be published in due course, but this note focuses upon a saltern that was probably Romano-British in origin.

The features directly associated with salt manufacture included structure [1838] and a large circular pit, [1815] (not shown on Fig. 1). The pit measured 1m in diameter and was located 0.75m to the north of the saltern. It was probably a storage pit for the brine.

The saltern was aligned north-south and measured 3.90m long by 1m wide, with a stokehole as the main heat source at the southern end of the structure and two flues to the north. Recorded as [1838] the feature was cut into the natural boulder clay. The edges of the feature were heavily burnt. The southern lobe of the structure was edged in stones and within this part of the feature there was a series

of graded burnt stones that stepped up a gradual incline towards the north end. Fragments of briquetage were recovered from the interior of the structure. It is suggested that a series of four trays or troughs (Fig. 1, shown in blue) were placed across the stones with hot air drawn beneath, from the fire to the flue, south to north.

The site is provisionally dated by a number of Romano-British pottery sherds found within features in the immediate area and I am awaiting spot dating of the ceramics. Radiocarbon determinations are expected in the new year from the glume and wheat chaff that formed part of the fuel for the furnace.

References

Sherlock, S J, 2021 “Early Neolithic salt manufacture at Street House, Loftus, north-east England” Antiquity 95, 648–669. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2021.25

Sherlock, S J, and Vyner, B E, 2013 “Iron Age salt working on the Yorkshire coast at Street House, Loftus, Cleveland” Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, 85, 46–67

Salt Making at Street House in 2023: Guided Walk Information

Excavations at Street House between 2016-2022 unearthed evidence for Neolithic salt making and settlement at Street House, near Loftus, occurring 6,000 years ago. In 2023, we aimed to understand more about the Neolithic activity at Street House, to find out if salt manufacture was occurring elsewhere in the area and to gauge how the process worked. At the south end of the site we have revealed evidence for a palisaded monument adjacent to the Neolithic saltern. Excavations in 2006-2007 demonstrated that salt making was occurring in the Late Iron Age and Early Roman period. In 2023 we have evidence for salt production within a Roman enclosure which is provisionally dated to the fourth century AD, that is, the Late Roman period. The evidence comprises a saltern hearth, with intense burning, flues and a large pit to store the brine brought from the shore (photograph).

Salt-making Experiments, 2-3 September 2023

On Saturday and Sunday 2nd - 3rd September we experimented with how to make salt from seawater collected from a coble off Whitby and then heated in a manner similar to the site discovered at Street House. This was a successful experiment. Salt is approximately a 3.5% component of seawater (or 35g of salt per litre of seawater). If we could get 30g from a litre of seawater that would be a good result.

Exp 1: 500ml brine solution was poured into tray 1, evaporated fully, and then repeated with another 500ml, then the crystalline product was weighed; 1 litre of brine solution was poured into tray 2, evaporated and then weighed.

Result: Tray 1 produced 2g of salt in 4 hrs 35 min; tray 2 produced 8g of salt in 5 hrs.

Exp 2: four trays (A-D) were positioned along the flue (with tray A closest to the fire). The trays were continually topped up to create a more concentrated solution as the day progressed.

Result:

Tray

A

B

C

D

Quantity of Salt (g)

9

37

15

38

Volume of Solution (l)

1.5

1

2

1

Time for Evaporation

5h 28min

4h 25min

4h 17min

5h 52min

Lessons learned from the experiment

Pre-warm the brine solution prior to filling evaporation tray.

The brine solution will naturally evaporate in the settling tanks (as found at Street House), resulting in a more concentrated (higher salinity value) brine solution.

Solution in the settling tanks or pits nearest the ‘furnace’ or fire source will be heated or pre-warmed.

It is important as to where the evaporation trays are placed along the flue relative to the distance from the heat source. In our experiments, the quality of the salt grains was affected. In Experiment 2, the solution in the tray positioned furthest from the fire evaporated the slowest and produced the largest quantity of salt crystals in both large and small (fleur de sel) grain form.

The depth of the saltern (fire and flue) would have been important for managing the wind at this site in antiquity, in order to control the heat flow down the flue and maintain a consistent temperature.

Lots of kindling was required! We burned over 3 wheelbarrows full of wood over two days for the two experiments each lasting approximately 6 hours.

Even on a warm, dry, sunny day salt crystals will absorb moisture at this location. Therefore, the drying process is important.

More than one tray would have been used at any one time in antiquity.

The ‘furnace’ area may also have been utilised for evaporation in antiquity.

The evaporation trays appear to be more efficient after first use.

Two methods were tested for evaporating the brine solution to see if more salt resulted.

More salt was produced during Experient 2: 37g from a concentrated brine solution of 42 parts per thousand (ppt) is a surprisingly efficient result, with even greater efficiency found with tray D, which evaporated more slowly at a lower temperature.